I’ve written on the five-room dungeon before. I’ve also talked about my use of prop theory as an aid in Mini-Dungeon design. If memory serves, I’ve even penned a diatribe explicitly titled “Introduction to Adventure Writing” in Adventure Chronicle Magazine issue #3. So instead of telling you about my process for writing Mini-Dungeons all over again, I want to tell you about my office.

Not the home office, mind you. I’ve just moved to Philly, and the home office is a barren holding cell for cardboard boxes on death row. It’s an exciting place for the boxes. They are plotting their escape even now. I suspect them of digging box-shaped holes through the drywall with little rock hammers, hoping to find freedom and Morgan Freeman voice-overs at the end of some Shawshank-esque septic hookup in my backyard. They have no choice. The box cutter is coming for them, and there’s no phone call from the governor offering a stay of boxecution.

But no. I don’t think my dull-as-dirt home office will be inspiring anybody with flights of fancy.

It’s the office office that has the stuff. And that’s because I’ve put all my art prints there. I collect dungeon maps, you see, and I have a very broad definition of what constitutes a dungeon. There’s a cutaway of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles’ sewer lair. There are twin ink drawings of Escher-style stairways careening around the inside of skull-shaped mountains, waterfalls roaring out the nostrils. I’ve got a copy of The Berenstain Bears and the Spooky Old Tree, which contains the first dungeon map I can remember loving as a kid. I’ve got a gorgeous Castle Ravenloft in full gothic glory. Narnia and Middle Earth and Discworld hang shoulder to shoulder with One-Eyed Willy’s pirate map, and I’ve got my eye out for a decent reproduction of the headpiece to the Staff of Ra from Raiders of the Lost Ark. But none of these are the jewel of my collection. That honor goes to a set of poster-size maps by artist Thane Benson.

One of these maps is called “Quick the Clockwork Knight and the Goblin Castle.” The other has no name, but I like to think of it as “The Gobblecock.” And that ludicrous name doesn’t belong to me.

I was walking my maps across campus to their new home. I’m a college professor by day. Just finished the PhD last spring, so it’s baby prof’s first semester over at Rutgers-Camden. By some enormous stroke of luck, they’ve allowed me to teach “Writing and Editing for Gaming” at the undergrad level. I was certain I would need tenure before I got to do that.

But, in any case, I was running a bit behind schedule that day. My beloved Goblin Castle and Gobblecock (whose etymology we’ll arrive at shortly) were tucked one under each arm. I was huffing and puffing my way across campus, and I was hoping to make it to my office for the drop-off before heading to class. No such luck though.

My usual parking spot is at the ass-end of campus. This is no one’s fault but my own. I’ve selected the spot because I like to start each day by walking through Johnson Park in Camden, New Jersey. I enter through a little trellis gate, where I’ve made it a ritual to say good morning to Pan each day. The little goat god is surrounded by icons of fairy tales and nursery rhymes. There’s Jack B. Nimble jumping over his candlestick. The Pied Piper setting rats on a merry jig. A billy goat Gruff or two rearing to fight on the far side of the reflecting pool. And across its own little bridge into Faerie, a gorgeous bronze of Peter Pan upon a torrent of Tinkerbells, all spiraling up on dragonfly wings beneath him.

So yeah. I’ve got plenty of reason to be late for class. That wasn’t my only problem, though. In addition to running behind schedule, I was also at a loss for the day’s lesson. My “Writing and Editing for Gaming” course is powered by geek networking and game cons. I’d gone to Gen Con 2023 with a specific goal in mind: to recruit as many industry pros as possible to serve as guest lecturers. My theory was simple: anyone can teach writing as a skill. But if you want to be a freelance writer, you need to understand what freelancers actually do beyond writing.

My colleagues at AAW Games were happy to pitch in. We’re friends outside of work, so that was an easy ask. What surprised me was how eager other game designers from across the industry were to help, too. I suspect their thought processes ran something like, “Wait a minute… you mean The Academy is interested in tabletop game design? What I do is valuable and recognized as a legitimate art form? Finally!” Meanwhile my own thought process went something like, “Wait a minute… all these badass game designers are willing to come and help out my students? I’m the luckiest prof in the universe!”

The guest lectures ranged in topic from micro-RPG design to marketing, and from broad industry overviews to the more esoteric challenge of designing a tabletop experience for mid-pandemic online audiences. After each lecture, I asked my students to write down a few “this is useful to me” design concepts they picked up from the talk. I intend to compile those into a handy reference doc at the end of the semester. It is, in my own humble opinion, a really friggin’ cool class. The only problem lies in coordinating all those game designers across multiple time zones. Despite their vast powers of imagination, game designers are only human. They have previous commitments and sudden, unavoidable conflicts just like the rest of us.

So, there I was with a recently canceled guest speaker, wondering what bit of my syllabus to rearrange and present out-of-sequence. I didn’t have a lecture prepped, so the bog-standard sage-on-the-stage option was out. My students had their own mini-dungeons coming due though… maybe some kind of design exercise? We’d already brainstormed dungeon concepts in a group critique kind of way, and they were well on their way to developing those into finished drafts. Maybe a group exercise, then? Yeah, that would be low effort on my part cool.

And that’s when I realized what I was holding in my hands.

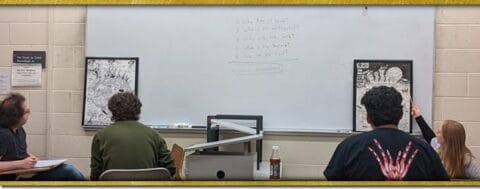

It is hard to read at this resolution, and my handwriting is a bit crap at the best of times. So, in the interest of clarity, in addition to my two dungeon posters sitting propped on the chalk tray, the following questions are written in the middle of the white board.

- Why does it exist?

- Who is our antagonist?

- Why are we here?

- What is the reward?

- How can we fail?

3-7 Encounters

Just like Mini-Dungeon writers at AAW Games, my students started with a pre-existing map. Their instructions were to answer those five questions, coming up with a basic pitch for their Mini-Dungeon in the process. As it turns out though, the “now come up with 3-7 encounters” bit was too easy.

The students on the left named that weird chicken dragon, The Gobblecock, and they invented encounters for every single critter and chamber inside that fell beast. The students on the right had a rock-solid quest hook, with our wandering knight getting drawn into the goblin castle thanks to the fabulous flying steeds roosting at the top. Get to the top of the tower, and you can ride off on your new mount, Jake Sully style (presumably minus the hair tentacle interface).

“Looking at a dungeon that tells a story was helpful,” said a member of Team Goblin Castle. “Seeing the hero and the action instead of empty rooms helped to jumpstart ideas in my own work.”

“It was the teamwork aspect that I took away from the experience,” said the inventor of ‘Gobblecock.’ “Listening to other people around you teaches you to be flexible with your own ideas.” They got a little taste of working within a team of co-creatives, and it was all manner of gratifying to watch them imagine together.

The exercise was helpful for the students, but I think it was even more helpful for me. By writing out those five essential questions, I could finally articulate what it is that I actually do when designing my own dungeons. I don’t just invent a place. I discover why it’s there. I imagine how our heroes came to be there, as well. What opposes them and what do they hope to gain? Pondering more interesting fail-states than “you all die and have to roll up new characters” helps me to imagine better drama. And with any luck, it will do the same for my students.

I am hopeful that some of the assignments due later this week have The Stuff. With a bit of feedback and a lot of polish, there’s a chance my students’ names will be right there beside mine in Mini-Dungeon Tome III. And if that happens, I will consider myself a very lucky teacher indeed.

Claire Stricklin

Mini-Dungeon Author & Game Professor

Darkness Rises, and the Time is Now…

Align with House AAW and be the first to uncover new quests, ancient powers, and revelations from the Underworld.